The people over 50 who are hitting the books

RNZ

17 August 2025, 9:50 PM

New Zealand food writer Julie Biuso graduated with a Master of Creative Writing from the University of Auckland in May, 2025. Photo credit:University of Auckland / William Chea

New Zealand food writer Julie Biuso graduated with a Master of Creative Writing from the University of Auckland in May, 2025. Photo credit:University of Auckland / William CheaWhether it's for the first time or a return to tertiary, people who are near or beyond retirement age still have the fighting spirit to head to university.

By RNZ Digital journalist Isra'a Emhail

When experienced broadcaster and food journalist Julie Biuso arrived at the University of Auckland campus last year, she felt a bit like an imposter.

“Although it was funny, I'd travel by ferry from Waiheke and then either walk up or sometimes get the bus. If the bus was crowded, people would stand up and give me a seat because they probably thought I was a professor. Little did they know.”

The now 71-year-old was the oldest on the Master of Creative Writing course by “quite a few years”, she says. The university describes it as a competitive degree, with only about 12 students accepted each year.

Last year, people aged 40 and above made up about 20 percent (75,890) of domestic students enrolled in degrees ranging from certificate level 1 to doctorate.

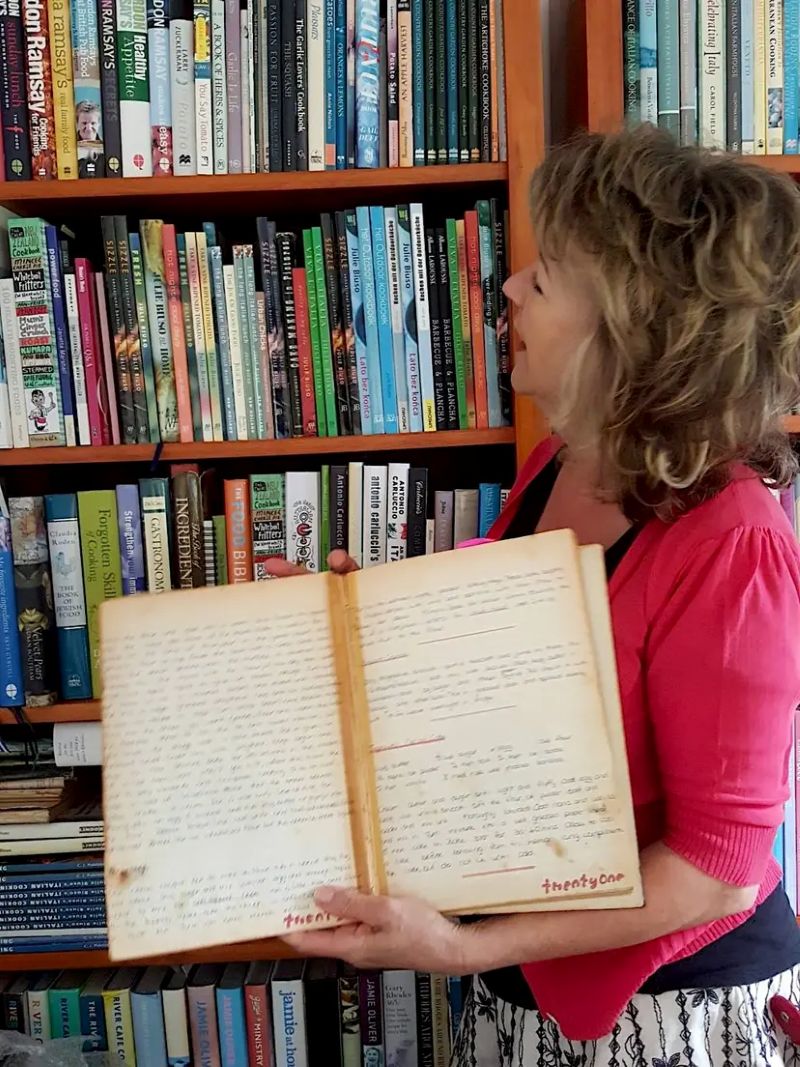

Julie Biuso looks at a shelf containing her cookbooks and hold holds her first ‘book’ of family favourites - written when she was about 10. Photo: Supplied

“I'd written 17 cookbooks in my career, and I've worked as a food journalist and broadcaster for 40 years. But I didn't have an English degree. So it was quite a lot of things to consider,” Biuso says of her decision to apply.

“I thought, I'll never know unless I have a go. So I started with the enrolment and it was so damned hard. It was like the proof and all the things that you had to do.”

Biuso, the youngest in a family of 10 children, has been on a journey around the world learning about different cuisines and honing her craft. But she always knew she wanted to write a novel.

It wasn’t until she moved to Waiheke Island about 10 years ago, when she separated from her husband, that her creative talent was unleashed.

“I think for a lot of women in particular, you've gone through that whole thing, you might have started university or done a degree earlier or not even gone at all and life gets in the way and kids and work and all that kind of thing. You find yourself in your late 60s and you think, well, do I take up golf or what do I do?,” Biuso says.

Julie Biuso with her first granddaughter, Remi, at the Parnell Rose Gardens, Auckland. Photo: Supplied

"I wish I had time now to study politics, I mean there are so many things I'd love to do. I've left my run a wee bit late but just think of something you’re interested in, because if you are interested, you’re halfway there, the learning is easy."

Biuso graduated in May and has completed her first draft of her novel. The best part of it all is how you feel about yourself, she says.

“It comes at a cost because you’re supporting yourself through a year, and a degree is not cheap on any level, but I urge people if they’re interested and they're considering it, to find some way to do it because it's got all the rewards, not necessarily financial, but I think as a writer, you're kind of used to not making a load of money in your career.”

Jane McCarroll says she's not earning a fortune, but she's always pumped to start the day at her job. Photo: Supplied

Aucklander Jane McCarroll knows all too well what it means to be a single parent whose sole focus is on providing for her whānau. She spent 30 years in the corporate industry in various roles before hitting a turning point in 2023, when she was made redundant a sixth time.

“I just lost the energy to try and fight the tide of having to explain why I shouldn't lose my job or respond to a consultation exercise that is moot at best.”

Her parents advised her to consider what it was she truly enjoyed doing.

“I've always just had to provide and chase money and sometimes [because of] the stress of all of that pressure, I would wake up in the morning and vomit before going to work and that would happen for extended periods of time.”

The 52-year-old is now in her second year of studying at AUT for a Bachelor of Education (Early Childhood Teaching). The sector fit her aspirations of helping parents and supporting mental health of tamariki.

"The first thing people say, ‘what do you want to do that for? Six figures to minimum wage? Like you know you're changing nappies?'.

“And I was like, yeah, yeah, yeah, but let's just think about this as a transition time and then what does the pathway look like? And I'll tell you what it looks like, it looks pretty f---ing exciting, way better than what it looked like trying to fight for my job and being ghosted.”

While juggling two jobs and full-time study, her parents have sometimes chipped in to support her too, she says.

“Just the feeling that I have when I go to work now, where I feel appreciated, I feel valued, I work with stakeholders that are hilarious, they're two and it's just such an engaging life.”

She’s excited for what the future holds, with lucrative job packages for early childhood educators overseas too.

“I love kids and I love seeing the sense of wonder. It's good for us too, to see the sense of wonder and the magic in everyday things.”

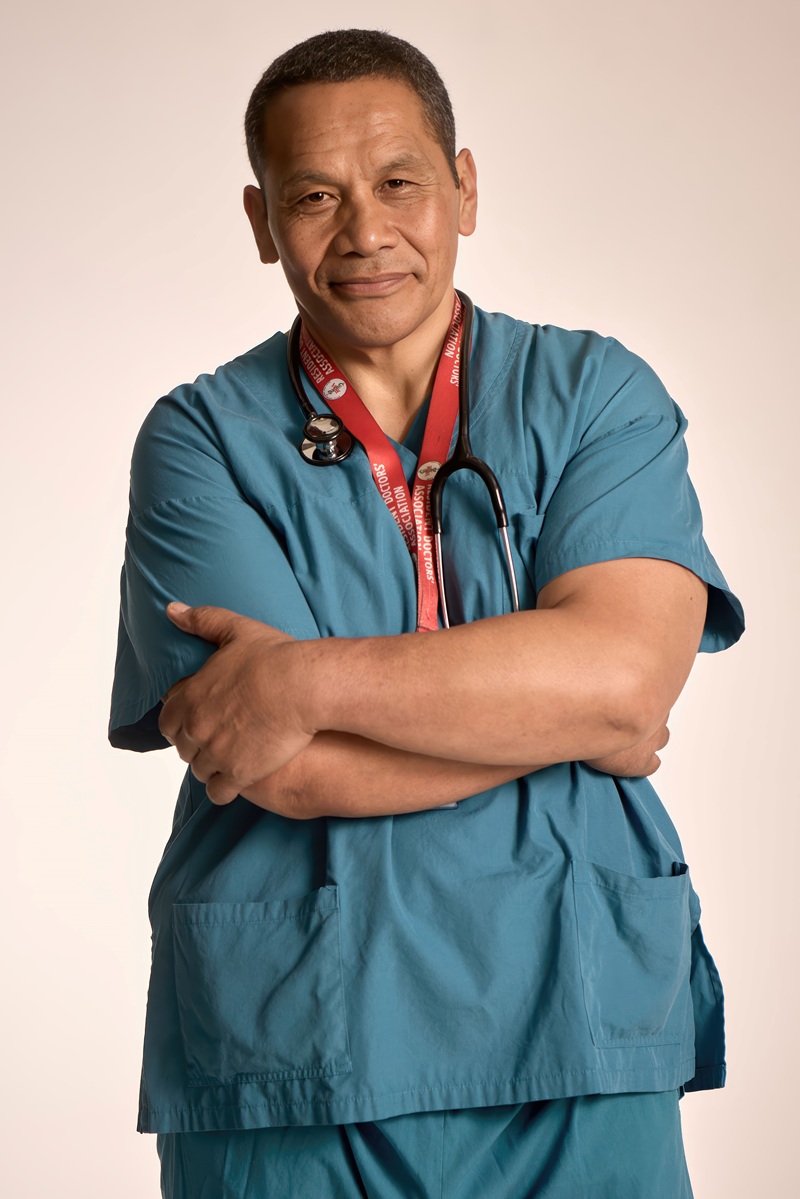

Dr Timoti Te Moke. Photo: Stephen Tilley

Just four months away from his final exams in AUT’s Bachelor of Health Sciences degree, Timoti Te Moke was facing a manslaughter charge and heading to the campus on meals of mainly rice and just enough money to pay for his rent and bus ticket.

He was ultimately found not guilty, but he continued studying throughout the trial. The practical component of his degree was delayed until the next year.

Having survived abuse and violence, a stint in prison and gang involvement, he was determined to graduate. Giving up was not an option, he says.

Listen here on Nine to Noon: The former gang member and prison inmate turned doctor

“I had to keep just pushing ahead. I had to make sure that I was doing the studying. Like when I get home, I just have my head in a book and of course I have to read over it five, six, seven, eight times for me to actually start picking it up because my head would keep wandering.

“Of course, it [the trial] affected me because I went from being in the top percentage of my class to being the last, but the thing is that the skills that I had developed over this life allowed me to survive, and that’s what I’m very, very good at.

“There have been a couple of times in my life, where I’ve been in situations where if I didn’t get up, I was going to die that night … I’ve experienced some unbelievable violence.

“The will to survive is irrepressible in me.”

Dr Timoti Te Moke says he wants to inspire the whānau to become doctors too. Photo: Supplied

After his paramedicine degree from AUT, he took a step further to become a doctor with a degree from Otago Medical School. The 58-year-old is now working as a house officer at Auckland's Middlemore Hospital, with plans to specialise in the ICU, which would take another five years to complete.

However, he’s clear about one thing. It wasn’t that he simply worked hard and became a doctor, he says, but he overcame societal barriers that pushed him to believe he could never achieve anything.

Before the manslaughter charge, the university had rejected his application three times.

"I’m more than used to having doors slammed in my face and being kind of shunned and rejected and that’s because my whole life has been hard,” Te Moke says.

“I'm a doctor now, but I should have been a doctor 30 years ago and the reason is because these barriers have been put in front of me through colonisation, through having to live in negative social determinants. Don't get me wrong. This isn't isolated to Māori, it’s just that Māori make up a huge proportion of it.”

His qualifications have opened the eyes of the younger members of his whānau, Te Moke says.

“They had a belief that Māori didn't have what it took to get in there. Not that they weren’t smart enough, but that those kinds of doors weren’t available for them,” he says.

“Now the plan is to make a family of doctors.”

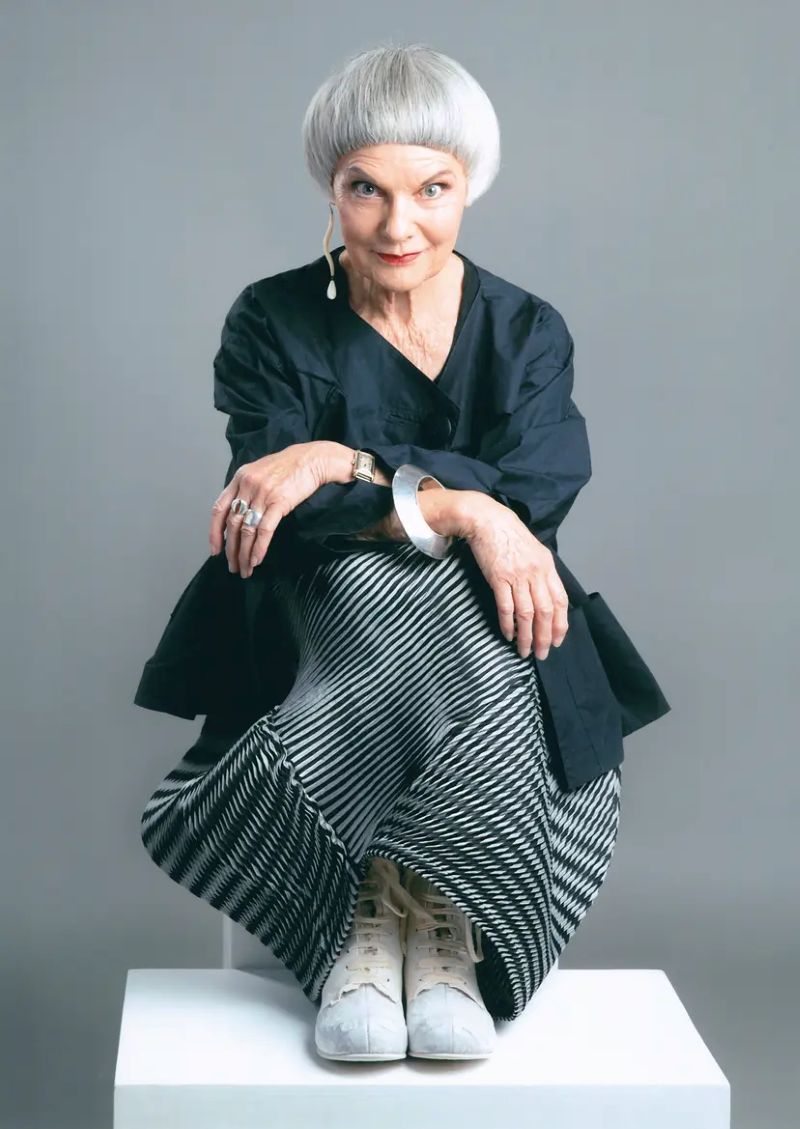

Rhondda Greig is a Wairarapa-based author and painter. Photo:Supplied

Rhondda Greig has established herself as a painter in the 84 years she’s lived. But there’s a certain memory from nearly 20 years ago that’s moved her so deeply, she’s attending the University of Otago’s Master of Creative Writing to pursue it as a writing project.

As an artist in residence at Scotland’s University of Aberdeen in 2006, she stumbled upon items that have a strong link to New Zealand.

“I always thought sometime when I come back to New Zealand, I want to creatively write about this or deal with it in some ways, because most New Zealanders will not know of this.”

Based in Wairarapa’s rural Matarawa area, where she has a studio, it wasn’t possible to drop everything and live in Dunedin for the course, which requires about 40 hours of commitment each week.

“What it has meant is that I’ve had to learn very fast, I can tell you that, the technical skills of managing Zoom meetings et cetera.

“I have been challenged in so many different ways but that’s good.”

When things get tough, she’s reminded of her mother - a trained soprano who couldn’t pursue her dreams.

"Often when I felt, ‘oh, I can't keep going, this is all too hard, I don't have enough money’ or something else has come up. I've always thought you have to. I have got to because I'm doing this for mum really,” Greig says.

“I would just be one of many thousands people who recognise that our parents didn't have the opportunities through education and encouragement perhaps in New Zealand that we have had.”

Going back to study is simply an expansion of her mindset of being a student of life and the compulsion in creatively expressing knowledge, she says.

“I was very conscious that I didn't want a younger person to have been denied a place on the course because they have a career and a future ahead of them.

“But I was able to deal with that by thinking, well, I have been deemed suitable. So what I am producing now … I'm feeling this [project] is something I can give back to New Zealand, not being grand about that, but it's an experience I have had and I know that when I'm gone, there won't be many people around who will remember it anymore.”

Greig had at a younger age been studying architecture but didn't finish that degree. She got married, became a mother and, instead, made a commitment to be an artist before going on to write five books and dabbling in poetry.

“Quite early on in my writing career, somebody said to me, ‘I can't understand why you want to write when you can paint, and you've established yourself as an artist’.

“For me, they've been in tandem. I mean, just because I can paint and I've been able to have a career as an artist, which has been fulfilling and wonderful, doesn't mean I have to shut down my voice.” - RNZ

NEWS

WHAT'S ON GUIDE